Josh Harper //

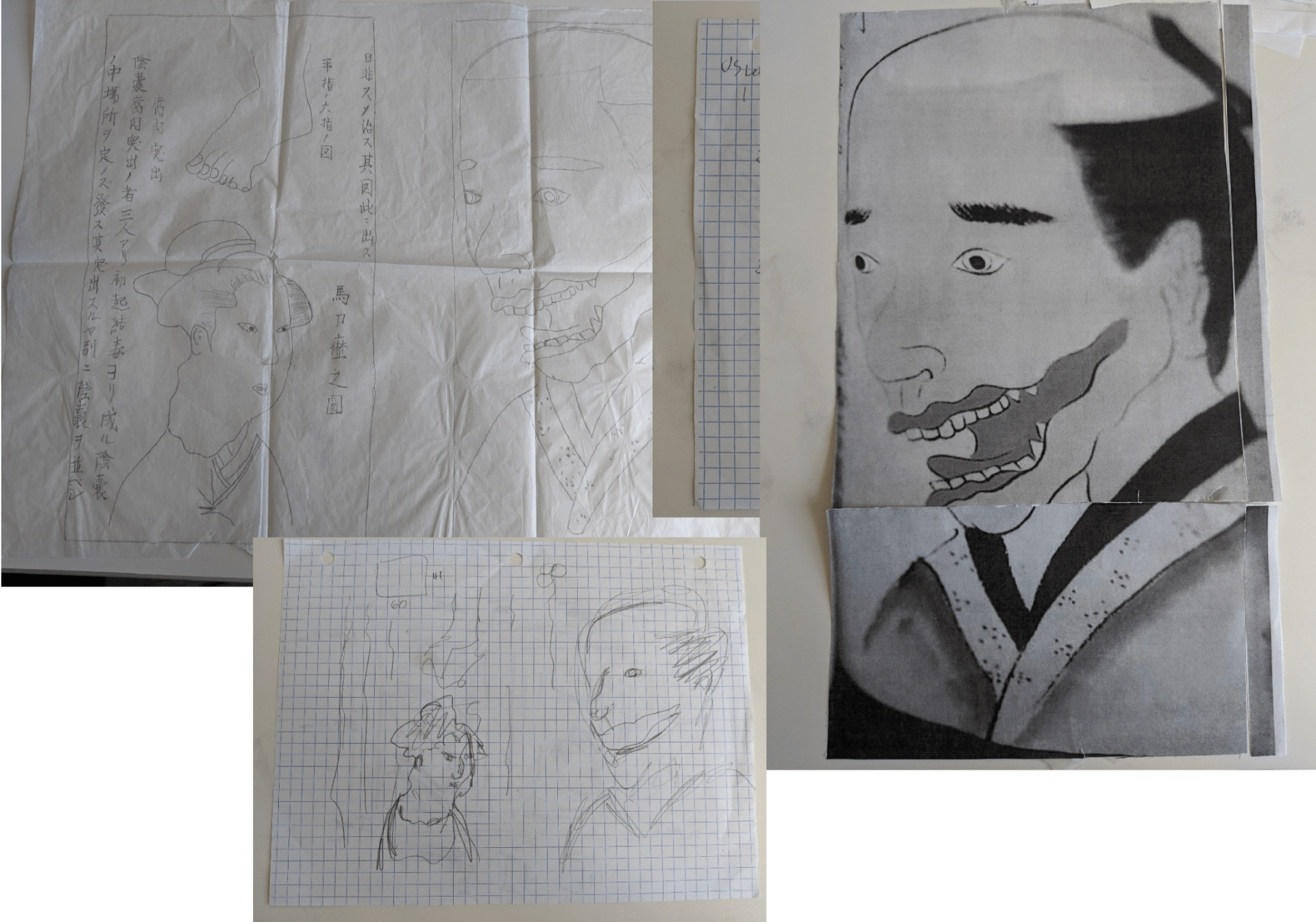

He is unwell. Wouldn’t you agree? His wild gaze, gaping mouth, unusually sharp molars. He needs medical attention. Thankfully, his surgeon, Seishu Hanaoka, thought the same. Hanaoka’s surgeries were… unconventional for his time. European scalpels, clamps, cauterization, in conjunction with Chinese physiological theories of the body.1 But Hanaoka did not travel to Europe. How, then, did he come to incorporate surgical techniques from such a faraway continent of the 19th century? Who gave Hanaoka these otherworldly tools, so easily incorporated in his disparate way of knowing?

The answer may lie, as many things do, with the Dutch. The Tokugawa shogunate happily encouraged knowledge-sharing with the “red-headed aliens,” as European sutures, clamps, scalpels burrowed deeper into Japanese bodily thinking. It was a strange partnership, this fusion of Dutch and Japanese thought.2 Rangaku, or Dutch studies, took centerstage and its European way of looking imprinted itself on the seen body in Japan. Though the Dutch didn’t have it all figured out. Their realist art style was a study on what historian Svetlana Alpers deems:

“Additive works that could not be taken in from a single viewing point…an assemblage of the world.”3

Thus, a fractured picture of the observed body.

Then how do you look at the body differently? If you look at the heart, is it just a heart? What changes? What we see is socially determined. Anatomical illustrations are socially determined. Sugita Genpaku, one of Hanaoka’s contemporaries, used a Dutch anatomy book to promote European illusionism into Japanese anatomical thought.4 For Genpaku, images of frayed nerves, blood vessels, stringy muscles, revealed a deeper truth his predecessors could not access.

Then again, Hanaoka did not commission this image. The man’s forced grin, skin peeling back in an unwavering smile. Sharpened molars. Eyes unfocused and unyielding, shaved head uncannily skewed. He’s frightened. Or frightening. One of Hanaoka’s students, Ken Matsuzawa, documented Hanaoka’s surgeries in his manuscript despite Hanaoka’s desire for utmost secrecy. But compare Matsuzawa’s image with Genpaku’s. No European illusionism whatsoever. No detailed nerves, blood vessels, stringy muscles. Where is the printed cross-hatching? The shading? Visual weight? Did Matsuzawa miss out on the memo of Rangaku taking centerstage in anatomical depictions?

Possibly. Or Matsuzawa could’ve been paying attention to a different Edo period trend, a fascination with strangeness in all its physical forms. The man in the image is a bit strange, no? Physiological afflictions became as historian Puck Brecher puts it:

“A metonym for ‘strangeness’ found within the sociocultural upheaval in aesthetics, anatomy, and medicine.”5

And quite an upheaval. A shogunate disintegrating, mines collapsing, geishas abounding.

Matsuzawa’s image is, in a way, an intersection of strangeness, aesthetics, and medicine. Strangeness in aesthetics as an emotional response to chaos. Perhaps Matsuzawa’s true intent lies in the name of the manuscript itself: Selected Dictations of Curious Records. And the afflicted man doesn’t stand alone, surrounded by a dismembered foot with six toes, a porcelain-white woman disfigured by neck protrusion. Neither of which Matsuzawa depicted in Rangaku-style. Perhaps intentionally. Certainly, Matsuzawa’s manuscript encapsulates a turning point in Japanese medicine: Rangaku takes hold, European trends become a point of reference.6 But the depicted man holds only an anatomical curiosity, perhaps never treated, still a bit garish.

NOTES

- Fujikawa, Yū. Japanese Medicine (New York, NY: AMS Press, 1978), 56.

- Fujikawa, Japanese Medicine, 44.

- Alpers, Svetlana. The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century (Chicago: The Univ. of Chicago Press, 2009), 122.

- Les, Charles, and Allan Young. “Between Mind and Eye: Japanese Anatomy in the Eighteenth Century.” Paths to Asian Medical Knowledge, May 1002, 23-24.

- Brecher, W. Puck. The Aesthetics of Strangeness Eccentricity and Madness in Early Modern Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2013), 5.

- Brecher, The Aesthetics of Strangeness, 4.

REFERENCES

Brecher, W. Puck. The Aesthetics of Strangeness Eccentricity and Madness in Early Modern Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2013.

Fujikawa, Yū. Japanese Medicine. New York, NY: AMS Press, 1978.

Leslie, Charles, and Allan Young. “Between Mind and Eye: Japanese Anatomy in the Eighteenth Century.” Paths to Asian Medical Knowledge, May 1992, 21-43. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520073173.003.0002.

Matsuzawa, Ken. A Facical Tumor to Be Excised with General Anesthesia. U.S Department of Health & Human Services, n.d. Accessed September 25, 2019.

CREDITS