Samantha Chao //

Is death transformative?

No science. No design. Nothing taken

Gently into his hand or your hand or mine,

Nothing we erect is our own.[1]

Lightning strikes a metal rod, sending sparks of electricity down its length towards a prone figure lying restrained on a metal gurney. Moments later, the hulking, malformed shape jerks awake. It is Frankenstein’s monster, an aptly named amalgamation of ill-fitting body parts. As he rises, he is undeniably alive. But is he human?

Scattered across literature are science fiction tales that depict the transformation of human bodies as they traverse between life to death. In these stories, bodies are split open and pieced back together in an effort to capture the elements of humanity.[2] This tradition emerges from a long, global history of scholars who use inanimate things to imitate life. Ultimately, the question they seek to answer is this: what makes people human?

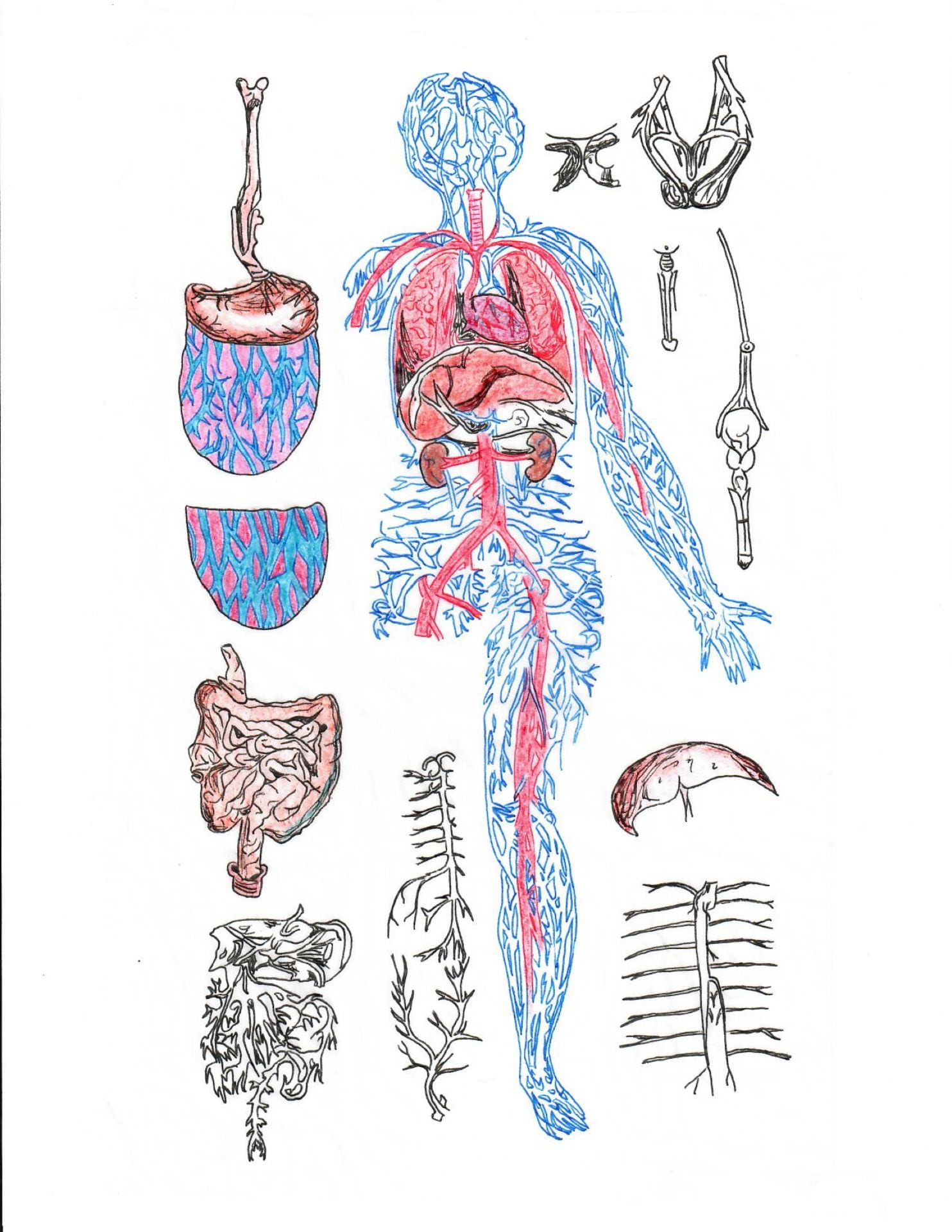

Death, the absence of life, necessarily transforms the human body as it loses the agency and identity of the living person. Scholars such as Andreas Vesalius take advantage of the vacuum left behind, projecting into it their own opinions on human life. To uncover secrets hidden inside the human body, Vesalius imitated life through his anatomical drawings. He would unearth bodies from their graves, dissect them, then draw them posed proudly like Greek statues. Self-professed to be Vesalius’s dispassionate observations,[3] they were actually reflections of his own preoccupation with deriving knowledge about people from the only bodies available to him, dead ones. His quest begs the question: what can the dead tell us about the living?

Modern attempts at bringing dead bodies to life can be seen through the traveling museum exhibit, Body Worlds, which visits North America, Europe, and East Asia. Similarly to Vesalius’s work, it also features bodies posed to imitate life. However, the medium of its art is the preserved bodies of donors, called plastinates, who are forever frozen in the middle of fencing, swimming, and playing team basketball.[4] As displays, these curated bodies are admired and consumed in an act historian Shigehisa Kuriyama would call, “lust of the eyes.”[5] This cannibalistic fetishization of dead bodies thus allows the aesthetic of death to inform imitation life, creating an uncanny affect through the disconnect between the object of observation, the plastinates, and the subject of study, living people. A thorny question arises: what does it mean to imitate life?

Thus far, people have attempted to replicate only the physicality of humans. Now, with ever-developing digital technologies, an era arrives in which the permeable interface between virtual and actual space filters personality and identity into the equation.[6] The show Black Mirror explores this in an episode called “Be Right Back,” in which a widow purchases a robotic clone of her husband, complete with personality derived from his social media presence in life. Despite this sophistication, however, he still lacks what differentiates machines from humans. Like the plastinates of Body Worlds, immortal and unchanging, he is too perfect. He does not age, become ill, or even offer dissension, let alone get angry. He is devoid of everything that makes people so unwieldy, which are ultimately the very things that make people human.

As we imitate life using the dead, we transform them into piecemeal, Frakensteinian monsters. We overlook their strangeness because want to see, to know just what makes humans tick. Can we ever recreate humanity? Perhaps not. Do we still want to try?

The labor of hands cannot

Hold Mind’s I.

Let them run amok.

Their souls may be ours,

But their bodies are not

Ours to banish.

Bibliography

- Hallam, Elizabeth. Anatomy Museum. Chicago, Illinois. :University of Chicago Press.

- Jericho Brown, “Dear Dr. Frankenstein”

- Shigehisa Kuriyama, “The Imagination of the Body and the History of Embodied Experience: The Case of Chinese Views of the Viscera.”

- Vesalius, Andreas, The Epitome of Andreas Vesalius. Cambridge, Mass. :M.I.T. Press, 19691949.

- Waldby, Catherine. The Visible Human Project: Informatic Bodies and Posthuman Medicine. New Fetter Lane, London. : Routledge.

NOTES

[1] -Jericho Brown, “Dear Dr. Frankenstein”

[2] Shigehisa Kuriyama, “The Imagination of the Body and the History of Embodied Experience: The Case of Chinese Views of the Viscera.”

[3] Vesalius, Andreas, The Epitome of Andreas Vesalius. Cambridge, Mass. :M.I.T. Press, 19691949.

[4] Hallam, Elizabeth. Anatomy Museum. Chicago, Illinois. :University of Chicago Press.

[5] Shigehisa Kuriyama, “The Imagination of the Body and the History of Embodied Experience: The Case of Chinese Views of the Viscera.”

[6] Waldby, Catherine. The Visible Human Project: Informatic Bodies and Posthuman Medicine. New Fetter Lane, London. : Routledge.