Tian-Tian He //

Imagine a woman. Don’t think too hard. What do you see? A portrait, a color palette, a sound, a body part, a vital essence?

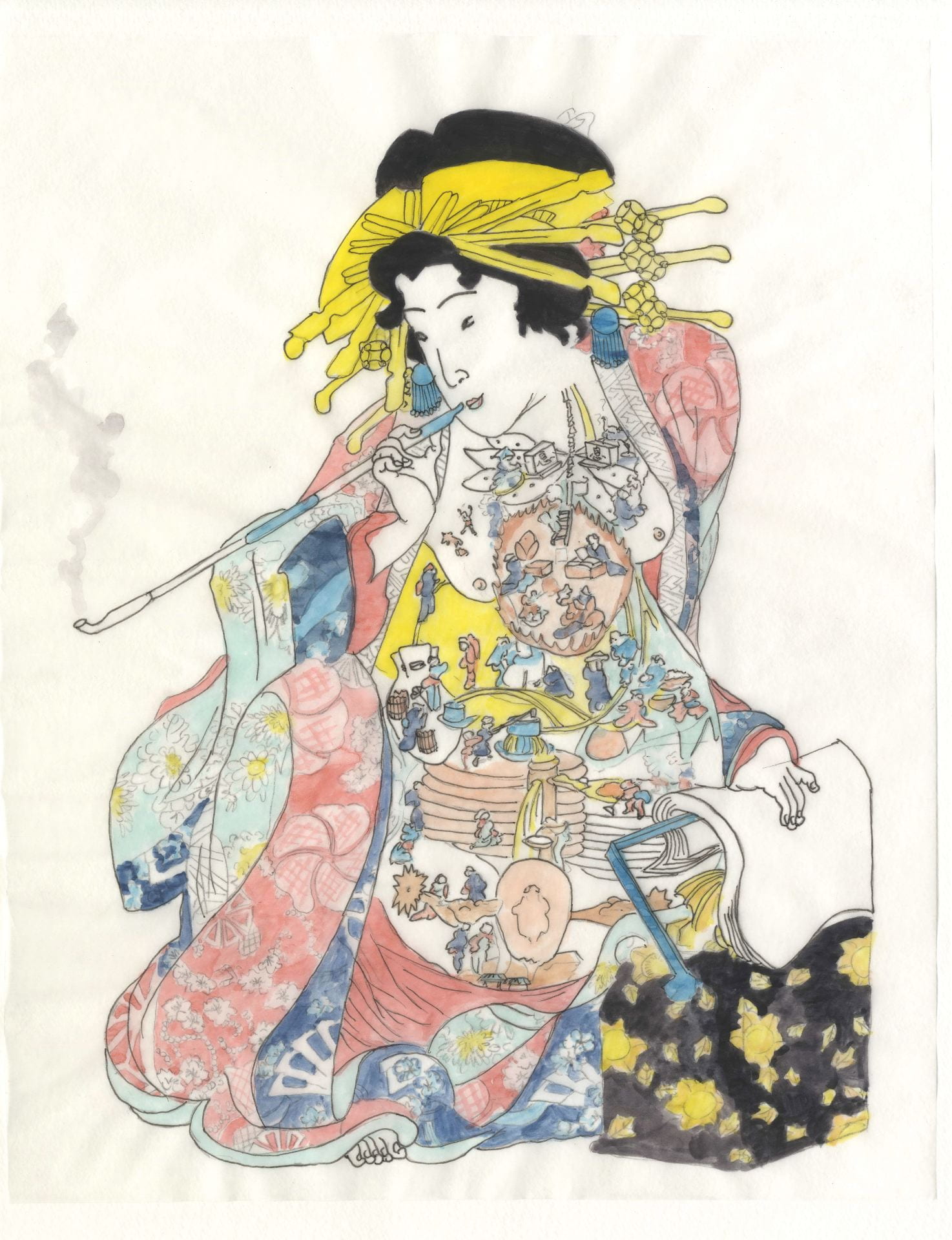

Perhaps she was the essence of a woman. The courtesan depicted in an 1850’s Japanese woodblock print titled Rules of Sexual Life showed us one version of a ‘real’ woman. This print claimed to educate the viewer about the functions of the organs by representing the body as a brothel. Each organ is a room, occupied by workers performing different tasks like grinding food in the stomach, fanning air in the lungs, and sweeping dirt in the large intestine. Additionally, paragraphs in the margins instruct the viewer on proper, healthy sexual behavior.[1]

“Rules of Sexual Life.” An image meant to teach viewers about the body, yet totally impossible, incomprehensible, absurd.

They carved her in flat, stylized curves – a romanticized woman dreamed up by men, recreated for men, propagated and sold to men.

Not only that, but dozens of little people and machines chug away inside her body.

How much can one really learn from a body full of metaphor?

For late 18th-century Japanese scholars Satake Shozan and Shiba Kokan, the answer would be nothing. “Rules of Sexual Life”, with its playfulness and frivolity, was the antithesis of what Shozan and Kokan considered to be quality art. They were believers of illusionism, the principle that art should resemble reality as closely as possible.[2] Kokan emphasized, “The marvel of pictures lies in their ability to allow one to directly see what one has not seen before. If, therefore, a picture does not faithfully copy an object as it really is, it loses its usefulness.”[3] According to Shozan and Kokan, in painting, no fun is allowed.

But to you, the listener, the idea of using metaphors to learn about a foreign concept is probably a familiar one. For example, in science class you might have been taught that…

[mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell audio clip][4]

Or, DNA is the blueprint of life, or that molecules are smooth plastic balls and sticks. To be honest, I still can’t picture molecules as masses of electron orbitals – only as balls and sticks, like little dumbbells.

Thus, metaphor is inevitable when we try to understand anything that we cannot directly see, like the inner workings of the body.

Which is better – knowing something, or knowing that something is like something else?

Is it even possible to separate the two? After all, according to the theory of social constructionism, the way we imagine certain things can alter or even create reality.[5] For instance, take the very idea that organs are distinct objects with distinct functions as depicted in “Rules of Sexual Life”. And we do need these frameworks to carry on with our lives. Because how else would we perform an organ transplant?

Perhaps we will need to be content with the knowledge that imagination lurks just underneath our realities, surfacing occasionally to make itself seen, like the mouth of a hungry koi fish.

NOTES

[1] Etsuo Shirasugi, “Envisioning the inner body during the Edo period in Japan: Inshoku yojo kagami (Rules of Dietary Life) and Boji yojo kagami (Rules of Sexual Life),” Anatomical Science International 82 (2007): 49, doi: 10.1111/j.1447-073x.2006.00159.x.

[2] Shigehisa Kuriyama, “Between Mind and Eye: Japanese Anatomy in the Eighteenth Century,” in Paths to Asian Medical Knowledge, ed.s Charles Leslie and Allan Young, 21-43 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 10.

[3] Kuriyama, 12.

[4] Wellcome Trust Center for Mitochondrial Research, “What are mitochondria?” May 9, 2016, YouTube video, https://youtu.be/7o0NkKez1AY.

[5] “Social constructionism,” Oxford Reference, accessed December 3, 2019, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100515181.